Around the World in Eight Trees

A blog to celebrate Arbour Day on 29 April

The trees looked after by INTO member organisations vary from Australian boabs to Caribbean mangroves; Japanese maples to British oaks, reflecting a wide range of different habitats, landscapes and climates.

Some have only been recently planted, restoring wild environments or replicating land management practices of the past. Others have lived through many centuries of change. And indeed, are museum-worthy in their own right.

Many trees moved across the world. Collected by plant hunters, species previously growing in Europe, or indeed botanical hotspots such as China, Japan and South America, were introduced in other countries. It is surprising that there are only about thirty native tree species in the UK.

We all know how important trees are to nature, wildlife and climate change. They are also vital for our health and wellbeing. And trees are part of our history and culture.

National trust gardens around the world are places where we can look after individual specimens, with fantastic stories. But we can also conserve old varieties and make sure there are new plants to replace dying trees.

And so in the spirit of Jules Verne and his account of Phileas Fogg’s travels of 1872, here are eight global tree stories to enjoy!

Our thanks go the Oxford Partnership Micro-internship teams we hosted in 2021 for ‘rooting out’ these stories, particularly Brooke Creager.

But what then? What had he really gained by all this trouble? What had he brought back from this long and weary journey? Nothing, say you? Perhaps so; ... Truly, would you not for less than that go around the world?

Eight global tree stories

In 1860, the Victorian government sponsored an expedition to make the first south-north crossing of Australia, a distance of 3,250 kilometres. Robert O’Hara Burke and William John Wills led the expedition from Melbourne and reached Coopers Creek by December that year.

Burke and Wills travelled north with two others, Charles Grey and John King, while four men remained at the Coopers Creek Depot.

However, when they did not return, the party who had remained at Coopers Creek was forced to decamp and trek homewards on 21 April 1861. Before they left, they carved or blazed messages into two eucalyptus trees, pointing to a cache of buried stores.

In fact, they left only hours before the return of Burke and Wills. They found the hidden supplies but were not able to make the journey home. Only John King survived, with the assistance of Aborigines until being found alive by a search party in September 1861.

The blazes on the ‘Dig Tree’ remain as a memorial to Burke and Wills’ expedition and a symbol of the bravery and hardships endured by Australia’s early explorers.

Other trees on the National Trusts of Australia’s Register of Significant Trees include the weeping paperbark associated with the spot where Captain James Cook beached the Endeavour in 1770; the Prison Tree in Derby, Western Australia, a large hollow Boab believed to have been used as a holding post for prisoners and which today symbolises the harsh treatment they often received; or the Christmas Tree, planted in Yankalilla, South Australia, in 1924 by Phillip Chenoweth, the local blacksmith, as memorial to his wife Mary and which is often decorated for Christmas by local residents.

On the plateau of the Sila region, there is a monumental woodland of 350-year-old trees that are 45 metres in height, with trunks 2 metres wide. This ancient wood features more than 60 Calabrian pines and sycamores planted in the 17th century by the baronial Mollo family, owners of the nearby farmhouse, which was donated to FAI in 2016.

The woodland was exploited over the centuries by shepherds to extract a flammable, tar-like resin from the trunks; it was a valuable resource in the 17th and 18th centuries, and was subject to numerous edicts issued by the government of Naples with a view to limiting the frequent threats to cut the trees down. In the Second World War, the land was expropriated and then reintegrated into the assets of the Italian Forestry Commission, which – together with the Mollo family – promoted the establishment of the Guided Biogenetic Nature Reserve with a view to studying, genetically conserving and protecting this immensely valuable historic and natural heritage. Today, human intervention here has the sole purpose of allowing nature to take its course and making it possible to observe the natural evolution of the woodland, offering a wilderness to animals that now live in very few other places in Italy.

The Giants of Sila are looked after by FAI – Fondo Ambiente Italiano, the National Trust for Italy.

Fundem, one of the INTO members in Spain, is removing non-native eucalyptus and restoring the local tree population. They have acquired a small plantation at Ulloa, Lugo in Galicia where they are replacing the eucalyptus with indigenous specimens: oaks (Quercus robur), chestnut (Castanea sativa), birch (Betula alba ), ash (Fraxinus excelsior), holly (Ilex aquifoilum), maple (Acer pseudoplatanus), wild pear (Pyrus pyraster), willow (Salix atrocinerea), laurel (Laurus nobilis), hazel (Corylus avellana) and cherry (Prunus avium).

Aside from the eucalypts, it is a relatively well-preserved area with an abundance of native forest. For this reason, eliminating these exotic specimens and reforesting with native species is of vital importance, not only at an environmental level, but also due to their impact on the landscape.

In addition, the farm has a spring that flows almost all year round. The eucalyptus trees have slowly but surely begun to dry out both the spring and the adjacent meadows themselves. The restoration of the native forest will reverse this situation.

In the woods of the Zoet Water in Oud-Heverlee is the baroque chapel of Our Lady of Steenbergen. They say that the community began worshiping here well before the chapel was built. There was a simple statue of Mary hanging from an oak tree near the Minne Spring.

Miraculous healings were attributed to the well, which brought with it an influx of pilgrims. In 1651, Lord Hendrik van Dongelberghe had the current chapel built, one of the largest in Flanders.

In 1975 the statue of Mary was stolen from the chapel, but that did not stop ‘The true friends of Steenbergen’ from continuing the annual procession on 15 August. After the death of the eldest daughter of the Vonckx-Spreutels family, the family took over the maintenance of the chapel, which marked the start of its revival and restoration. Thanks to an extensive partnership with, among others, Erfgoed Vlaanderen, the chapel of Steenbergen received a full restoration and on 26 May 2006 Cardinal Danneels reconsecrated the restored chapel.

The tree may be gone, but the story lives on. And the Chapel of Steenbergen is now looked after by INTO members, Herita.

The Millennium Forest is one of the most ecologically important places to see on St Helena Island, with its varied species of endemic plants mainly the Gumwood. It opened in August 2000, and covers more than 38 hectares. Today, islanders have planted thousands of trees and it is a popular tourist attraction for the Island. The goal is to recreate the Great Wood that was once on the site before it was destroyed by settlers and invasive species.

50 years after Britain’s colonisation of Saint Helena in 1659, the Governor complained: ‘The Island in 20 years time will be utterly ruined for want of wood, for no man can say there is one tree in the Great Wood, or other wood less than 20 years old. Consequently it will die with age.’

The Great Wood was the largest expanse of forest within St Helena’s 123 square kilometres (47 square miles). As such, it was home to an unknown number of birds, plants and insects now extinct. The Great Wood was entirely destroyed as settlers cut down the trees for firewood, used the bark for tanning – thereby unnecessarily killing them, and allowed goats and other introduced animals to graze on the saplings.

A project was launched in 2000 to reforest the area again. Virtually every Islander paid for a tree with many of them planting their tree themselves. During this first phase about 3,000 trees were planted, a car park laid out and a gatehouse built. By 2012, about 35 hectares have been planted with 10,000 trees. The total land area designated for reforestation has been extended in the course of the last thirteen years and is now 250 hectares. Currently there are 6,000 gumwoods growing in the Millennium Forest. An estimated 55,000 further plantings are required to cover the entire area designated for forest.

Calke Park was designated a National Nature Reserve in 2006 in recognition of its importance to nature conservation. At the time, there was a competition to name its oldest tree and this veteran oak became known as the Old Man of Calke. He’s over 1,000 years old and is a relic of the ancient wood pasture that predates even the abbey itself. Many centuries of pollarding have given him a squat, tree-man appearance like a character from a fairy tale.

Ancient and veteran trees like this are nature reserves in their own right thanks to the variety of valuable habitats found within their minibeast-scale landscapes of nooks and crannies. Dead and decaying wood are especially important for specialised invertebrates that rely on this increasingly rare habitat.

Ancient and veteran trees like this are nature reserves in their own right thanks to the variety of valuable habitats found within their minibeast-scale landscapes of nooks and crannies. Dead and decaying wood are especially important for specialised invertebrates that rely on this increasingly rare habitat.

Other stories from the National Trust’s recently published book, 50 Great Trees include an old sycamore tree growing at ‘Sycamore Gap’ on Hadrian’s Wall, which was named England’s Tree of the Year by the Woodland Trust, had a staring role in the 1991 film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves; the apple tree at Woolsthorpe Manor that inspired Isaac Newton’s thoughts on gravity; the 2,500-year-old Ankerwycke Yew near Runnymede, the oldest tree in the Trust’s care and may have witnessed the events around the sealing of the Magna Carta in 1215; or another old sycamore on the village green at Tolpuddle where the workers met to form a union and protest against their meagre wages in 1834.

In 2021, the National Trust of Slovakia began a new international project, highlighting ancient trees. Wise Trees seeks to establish long-term cooperation between historic and botanic gardens in the Slovakian-Hungarian border area. The aim is to improve garden tourism, which could have a decisive role in the region, where more than 60 gardens have been opened for the public. And the main feature of the project are the ancient trees living in these public gardens.

The National Trust of Slovakia is working with the Hungarian Association of Botanic Gardens and Arboreta in preserving, examining, healing and interpreting ancient trees for the benefit of the local community and tourists.

Over the course of the project, 80 wise trees will be examined, with a focus on ten particular specimens which will be rehabilitated and celebrated.

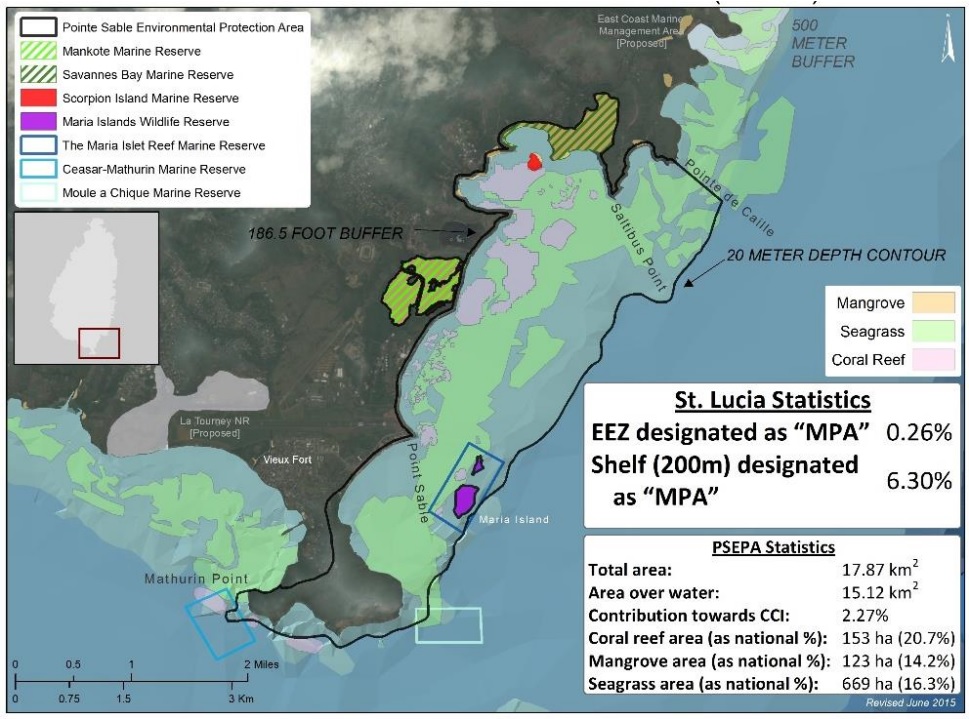

The Saint Lucia National Trust has been collaborating with the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States and The Nature Conservancy on two projects aimed at contributing to the restoration of the Ma Kôté Mangrove in particular, and mangroves in Saint Lucia in general

The coastal areas managed by the Saint Lucia National Trust comprise networks of interconnected systems including beaches, sea grass beds, coral reefs, dry forests, mangroves and off shore islets. These provide safe habitats for threatened terrestrial reptiles, marine turtles, migratory and resident land and sea birds, fish nurseries and forest products, some of which sustain livelihoods.

However, they have suffered severe coastal degradation and damage to coastal infrastructure and ecosystems over the last decade as a result of both natural events, including storm surges, hurricanes and flooding. Unsustainable land use activities have either intensified the impacts of natural events or eroded the natural resilience of the coastal resources that would normally offer protection to these coastlines.

This project seeks to enhance the climate resilience of targeted coastal ecosystems through improved health and management. One of the strategies employed under this project is to assess the adaptive capacity and ecosystem value of the mangrove forest. Mangrove ecosystems help stabilize coastlines, reduce the impacts of strong winds, and prevent erosion from waves and storms. Apart from serving as a breeding, feeding and nursery habitat for fish and other terrestrial and marine species, they also supply nutrients to nearby ecosystems such as coral reefs and seagrasses.

The Saint Lucia National Trust’s work to restore the severely damaged Ma Kôté mangrove forest will protect the southern coast of Saint Lucia from impacts of climate change like flooding and erosion, in addition to serving as habitat for juvenile fish. Across the whole area, about 4,000 mangrove seedlings were planted and nearly 100% are growing successfully, with a full recovery of the forest now expected.

Trees and the climate

The climate crisis is the single biggest threat to our global heritage and trees have an important role to play in the challenges ahead.

Find out moreINTO members featured

Australia

Italy

Belgium

St Helena

UK

Slovakia

Saint Lucia