Essential work in heritage across the globe

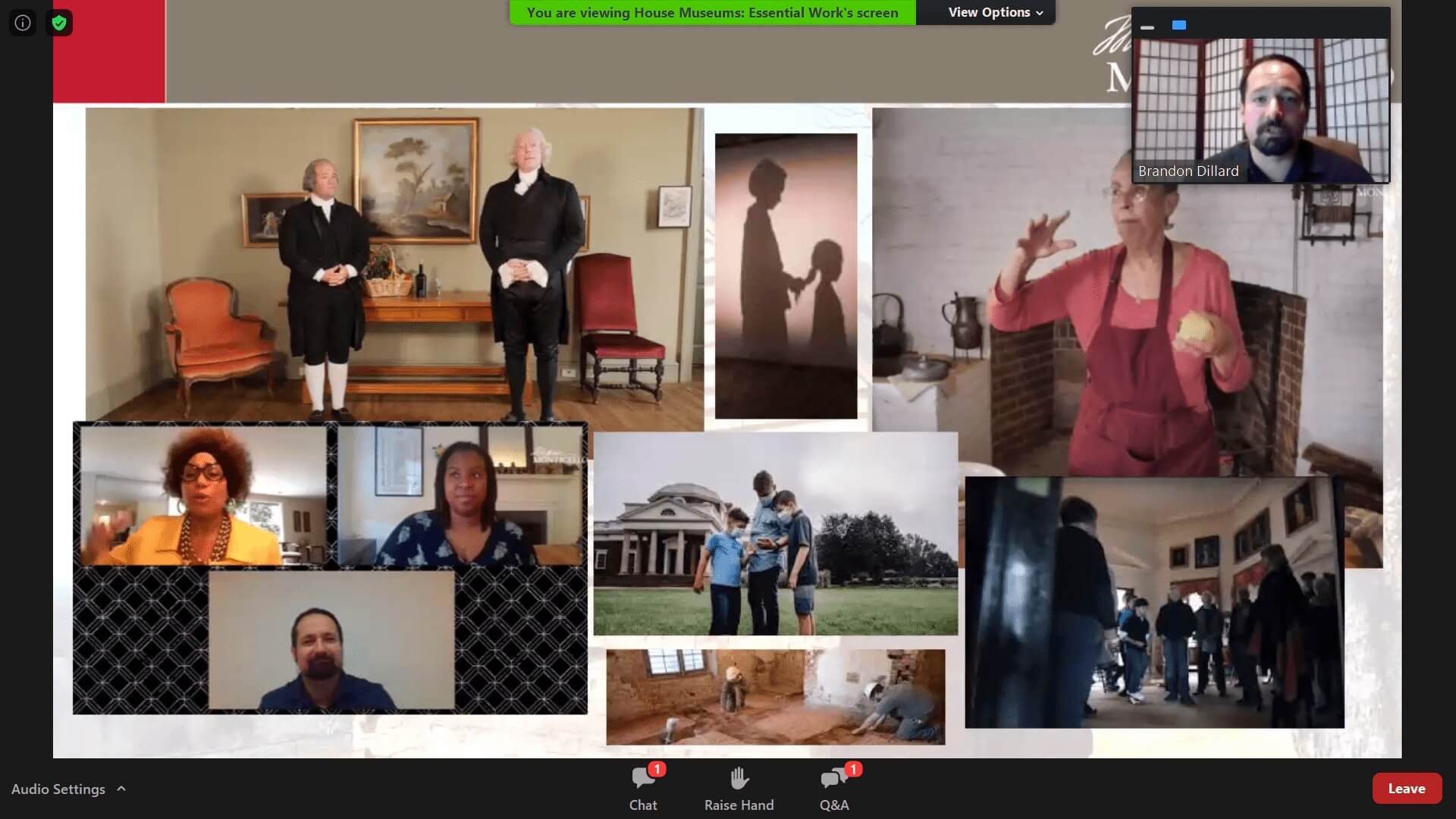

Last Saturday I tuned into an excellent virtual symposium hosted by the Wilton House Museum. Entitled ‘House Museums: Essential Work’, it recalled our Board discussions last month. When we talked about how to make our work essential in the post-covid world. Something Ruth Abram then highlighted in her presentation. But also, recent debates across our sector about the importance of telling the whole story.

Essential work at Monticello

First up was Brandon Dillard, Manager of Historic Interpretation at Monticello. This is the home of Thomas Jefferson, the third President of the United States, his family and slaves. It was fascinating to hear about the first tour guides when the property opened in 1923. African American men, dressed in elevator-operator style uniforms, who worked for tips. Telling stories of Thomas Jefferson that had been passed down to them. In the 1950s they were laid off and replaced by wealthy white women. Their tours focussed almost exclusively on the decorative arts. An approach that was standard for the day. And which caused some understandable animosity with the local community.

Family Gatherings

A local community comprising descendants of enslaved people who saw that their stories were not being told at Monticello. In the 1980s and 90s, through new research and archaeological digs, much more was learned about the plantation house. An oral history project called ‘Getting Word’ recorded the experiences of 200 descendants. Furthermore, the team introduced a tour focussed on slavery. Not an optional extra but a fundamental part of the visit. And still today, a general entry ticket to the house includes a tour of the house, the slavery tour and access to the grounds.

In 1997, the first ‘Family Gathering’ was held for descendants of Thomas Jefferson – with his wife and other people – and the slaves who lived at Monticello. (These have continued to this day and in 2018, 300 people came.) The story of Sally Hemings and questions over who fathered her children was both fascinating and poignant.

Telling the whole story

Historians did eventually settle that – from DNA evidence and oral histories – Jefferson was indeed the father. And since 2000, tour guides at Monticello are supposed to include that fact in every tour. (Although it was interesting to hear from Brandon that they don’t always.)

When the house was opened in 1923, it was bowdlerised. Many structures were changed, including Sally Heming’s room which was turned into a bathroom. “History was created in a very public way”, said Brandon. Reconstruction of the gardens began in the 1980s. Followed by physical reconstruction (including enslaved people’s homes on Mulberry Row) in the early 2000s. In 2015, Monticello invited the Family Gathering descendants group back for a ceremonial opening. They have become an important touchstone for the property as it moves forward. There was also a big conversation about this place which features behind Jefferson on the back of a US Nickel.

The team have now finished the restoration of the South Wing, where Sally Hemings lived with her children. And there is an audio-visual experience which uses the words of her son, Madison Hemings.

Are Americans falling out of love with their landmarks?

Brandon told viewers that visits to historic sites American are on the decline. People are falling out of love with America. At least, they don’t like the new way the story is being told: “Older Americans who grew up on the American story, and felt its magic, now grieve for a lost sense of American exceptionalism.” I think many of us can recognise that sentiment amongst our own audiences.

Brandon’s response is “If we’re not talking only about the past and not what it means today, what are we doing?”. And he also noted the importance of engaging with a broader demographic of visitors through the stories we tell.

Visits to National Park Service historic sites is conversely on the rise. (From 56m in 1979 to 109.5m in 2018 – a 95% increase.) Places like the Boston African American National Historic Site, Lincoln Memorial or Pearl Harbor National Memorial. The Smithsonian is also welcoming more visitors. It all depends on how and what stories are being told. “Places that are telling more complicated stories are getting more visitors.”

Resistance and backlash

When surveyed, 15% respondents said Monticello was whitewashing history. 15% felt they were besmirching Jefferson’s memory. And 70% thought they were doing OK.

Monticello is on the outskirts of Charlottesville, Virginia, which came to represent divisions over Confederate monuments in 2017. Brandon believes Monticello and the heritage sector need to be more out front of this conversation. (See the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s statement on Confederate memorials here.) He mused about the difference between a monument and a historic site. Adding that his board has wondered when ‘they were going to come and tear down Monticello’.

More to come …

I had wanted to cover the whole symposium in this blog. But it was impossible to cut short the Monticello story as it feels so relevant to all of our work. As I wrote in my introduction to our ‘Arms Wide Open’ report last year:

“But what does it [cultural diversity] mean to us, the National Trust movement, in practice? At our sites and in our work, we want all people to feel welcome. Wherever they come from, no matter the colour of their skin, faith, language, age, sexual orientation, ability, culture or heritage. But what about the more complicated questions relating to cultural diversity? How to balance the different sites and values recognised by diverse groups? What skills do we need to develop to better understand the heritage issues of different communities? Is the demographic of our profession a problem? And what can we do to build trust?”

We are all grappling with these questions: Is our work essential? How do we make our work more essential? What do we need to do to make the stories we tell more inclusive? How can we be more welcoming?

Monticello is an inspiration to us all, although I’m aware that many other sites, including nearby Montpelier, a National Trust for Historic Preservation historic site, as also dealing brilliantly with these issues. I’ve mentioned it in a previous blog, but the ‘The Mere Distinction of Color‘ exhibit at Montpelier is a new type of slavery exhibition which tells a more complete American story.

I’m going to have to write another blog (or two!) next week to cover the rest of the event. Thanks to Franklin Vagnone for alerting me to the event and to Wilton House Museum for having the foresight to host it!

Additional resources

- Arms Wide Open (report from INTO Bermuda 2019)

- Telling the full American story (National Trust for Historic Preservation)

- Addressing the histories of slavery and colonialism at the National Trust (England, Wales and Northern Ireland)

- Throwing new light on difficult histories (National Trust for Scotland)